When Miami Metro magazine named Italian-born Massimo Rizzo “Best Doorman on South Beach” and dubbed him “the prince of darkness,” it validated an eight-year history of hard and honest work in one of the world’s quirkiest and most powerful trades—guardian of the velvet ropes—the point of entry into South Beach’s most exclusive nightclubs.

In the modern history of South Beach, no one has done it better or been more heralded for his charismatic, discerning presence than the 35-year-old Rizzo, an ex-model and actor who holds two law degrees and owns a sports agency that represents professional basketball players.

Born in Tarando, Italy, Rizzo, who promoted and co-owned nightclubs in his hometown and throughout Italy before migrating to South Beach to attend the University of Miami Law School, began his illustrious second career in the early 1990s at The Butter Club, located on lower Washington Avenue where Bash stands today. When DJ-turned-club-owner Eric Omores bought the failed Butter Club and transformed it into Bash, whose celebrity backers included actor Sean Penn and musician Simply Red, Rizzo signed on to work the door and help with promotions. Rizzo calls it “the Miami Vice era. If you didn’t have a nice suit on, you weren’t getting in.”

Over the next several years, Rizzo mastered the art of velvet rope-style doormanship at Bash and later at the fabled Living Room, which ranks historically as the hardest place in town to get into. “They called us the door Nazis,” he says with a chuckle. But, on a good night, he earned $2,000; met countless beautiful women; and most important, learned the arcane, and sometimes mysterious principles of velvet rope management.

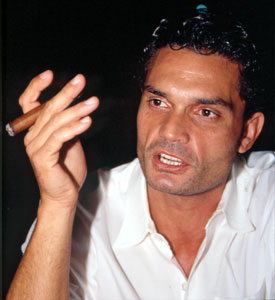

“It’s very easy to play tough guy and say no to everybody,” he says, puffing on a cigar at Lincoln Road’s Segafredo Cafe. “But the thing down here is, you never know who you’re dealing with. There may be a guy who looks like a bum and he’s a freakin’ multi-millionaire, about to blow fifteen or twenty grand in a club. You can cost the owner a lot of money if you make a mistake.”

“It’s very easy to play tough guy and say no to everybody,” he says, puffing on a cigar at Lincoln Road’s Segafredo Cafe. “But the thing down here is, you never know who you’re dealing with. There may be a guy who looks like a bum and he’s a freakin’ multi-millionaire, about to blow fifteen or twenty grand in a club. You can cost the owner a lot of money if you make a mistake.”

The ability to avoid mistakes requires developing what Rizzo acknowledges as a rare and eccentric set of skills. Often, however, such skills are characterized by intuition as much as anything, he says.

Massimo says he can tell when a potential patron, male or female, is still 20-30 yards away from the rope whether he or she will get into the club. “I scout them while they’re still a distance away,” he says. “You look for people who are good-looking, or funky-looking, or interesting-looking. And you look for people who know what the club is about.”

Not everyone belongs in every club.” Not even people with big money to spend are guaranteed an opportunity. Why not? “As far as the approach goes, I would leave attitude at home,” says Rizzo. “Very often, you can have the best-looking people and it looks like they have money, but they have the worst attitude. So, sure enough, they wait.”

Another sure way to ensure a long wait is to proclaim that you know the owner. “That’s the worst thing to say,” Rizzo says with a smile. “The next worst thing is ‘you don’t know who I am.'” He laughs heartily. “That’s when I’m an asshole.”

The first rule of good-status citizenship in clubland is “look good,” Rizzo says. “A club is about looks, about appearance. So, look good. If God didn’t give you the right cards, there’s not much you can do, but look the best you can.”

On the other hand, he says, expensive clothing in and of itself is no guarantee of success either. “You can have a lot of money and waste it on Versace suits and still be a peasant, look like one, behave like one, which means I don’t want you in the club. So, it’s not just about money,” he says, shaking his head.

In the end, Rizzo says, the game is all about mutual respect. A doorman who acts with respect and a potential patron who acts with humility are a marriage made in heaven, he says. “I’ve been called all kinds of names,” he says wearily. “It can get very personal. “It can also get quite dangerous, he says, like when huge crowds used to surge forward at The Living Room after the fire marshal had barred the entry of any additional customers. Fearing for their safety, Rizzo and his fellow doormen pushed back—and prevailed.

“It’s definitely a position of power,” Rizzo says of life at the velvet rope. “But you have to know how to use it. It shouldn’t go to your head. Respect for everybody is important, but you have to create your territory. I don’t let anybody touch my rope, owners and managers included. Everyone has to understand that once they cross the threshold, once they’re between the ropes, that’s my territory. Otherwise, it’s anarchy. I like dictatorships for some things, and the rope is one of those things.”

Today, Rizzo holds court at the ropes of mega-club Level, as well as fashionable new restaurant-lounge Pearl, co-owned by Eric Omores, who gave Rizzo his start at Bash. Rizzo points out that inexplicably, Americans do not make good door dictators. “You have to be able to get along with all different kinds of people from all different kinds of places,” he says. “For some reason, Americans are not very good at it.” All of the good doormen—Fabrizio at Crobar, Sergio at B.E.D. and Laurent at Nikki Beach Club—are European, Rizzo notes.

As for himself, he says is getting too old for the late-night hours and womanizing of the nightlife scene. Regardless of how late he stays out, he is up at 8:30 every morning working at his sports agency, Prosport International, Inc. He presently represents professional basketball players in the Continental Basketball Association and International Basketball Association. He dreams of placing players in the NBA.

This season, Rizzo and fellow velvet rope king Laurent Bourgade, also a veteran of The Living Room, are promoting a “house party” evening at fashionable new restaurant-lounge Touch. Rizzo says he also wants to open a small club, despite his failure and loss of $20,000 several years ago with a lounge called Exhibit in the space where B.E.D. is today.

For fun, he sits in the sun or goes bike-riding. He is perpetually at work on repairing a 1971 Vespa he acquired on a lark. He is also refurbishing a home he bought in Normandy Shores, on the same island where Eric Omores—who now owns Nikki Beach Club, Pearl and Lemon Twist restaurant in addition to the long-running Bash—is a VIP neighbor.

Rizzo says that given his long history here, with its ups and downs, successes and failures in the club business, he is happy with the maturing destination he sees. “I think the beach is finally reaching a balance between it used to be and what it is becoming, between quality and commercialization.” Still, he says, the club business remains brutally competitive. “Now with the new season beginning, we have all the grand openings of the new clubs,” he says. “Then in March, you have the grand closings. By May, you can tell who did their job properly.”

For the new season, Rizzo says he likes the chances of Michael Capponi’s new 320 and the soon to open Rain, where Groove Jet used to be. For fun, Rizzo hangs out at Crobar.

The moral of the story on ever-changing South Beach, he says, is that perpetual change is a cultural badge of honor. He also takes on the principle as a sort of personal mantra. “You can’t rest on your laurels,” he says. “You have to stay on your toes.”