Darkly handsome Dana Keith, who’s done everything from modeling for Gianni Versace to managing a performing arts center in a restored 1931 movie palace in Santa Barbara, is the driving force behind the new Miami Beach Cinematheque, which opened in July in a small building on South Beach’s Espanola Way.

There, in a little screening room in a restored 1925 Mediterranean Revival hotel, Keith and his cohorts from the Miami Beach Film Society plan to show unconventional programs of experimental films, Latin films, foreign films, gay and lesbian films, non-narrative films, and classic silent films—as well as dance performances and other events.

A veteran showman who, for the last decade has presented classic South Beach movie extravaganzas, such as the incredible Esther Williams Film Festival held poolside at some of the city’s greatest hotels, and an Indian film screening preceded by undulating classical Indian dancers, Keith says that for an alternative movie program to work in South Beach “it has to be fun.”

Keith is a dedicated film scholar, who has amassed a museum-quality collection of rare film posters, vintage movie programs and other documents dating all the way back to a screening room invitation from Thomas Edison, inventor the movie camera. Keith is intent on making the Miami Beach Cinematheque a center of cinema scholarship and education.

The screening room, still under construction at the time of this interview, is at 508 Espanola Way, in the heart of a unique, old-world-styled “Spanish Village” development built in the mid-1920s as an neighborhood for artists and writers. For decades, it has also been an entertainment district amassing quite a reputation. Notably, it is said, Desi Arnaz taught America to rumba here in the 1930s.

South Beach Magazine writer Bill Wisser recently spoke with Keith at the screening room about everything from the lure of cinema, to his partying experiences with celebrities, to his views on the rapid commercialization of South Beach.

Dana, show us around the cinematheque.

This will be the interior screening room. As you can see, it’s very intimate. And right through these doors here will be our exterior screening room, which you’ve experienced. [He points to a charming, tree-lined outdoor courtyard of the building where a few weeks earlier I’d seen a classic Bollywood epic from India which the film society had projected on a cloth screen strung up under the stars].

-from the MBC Archive

This location… this building… was chosen specifically because of the charm and kind of European pedestrian feeling of Espanola Way. I really can’t imagine this type of cultural venue anywhere else besides Espanola Way. Lincoln Road is well beyond this type of thing now and obviously Washington Avenue [site of many bars and nightclubs] wouldn’t be appropriate for this . . . [But] it fits in so well here. We’re right next to A La Folie Cafe. It goes along with the new Spanish restaurant opening up on the corner. There’s a kind of a West Village or St. Germain Des Pres feeling here.

How many people will this room seat?

Approximately 50, and 50 outdoors… it’s perfect for film festival panel discussions, it’s perfect for press conferences, or maybe for opening receptions.

What are the economics? Let’s say for an Italian theme night, maybe you show La Dolce Vita and you have a micro-cinema that seats 50 people, and you’re going to rent a film. Do you get a 35 mm print?

Along with the whole concept of alternative space comes alternative formats of presenting—instead of 35, we’ll be exhibiting by DVD, by video, by 16 mm, and eventually by digital, which changes a lot of the prices.

-from the MBC Archive

From the viewpoint of a film purist, is this less of an authentic experience than viewing a 35 mm print in a theater? After all, anyone can go to Blockbuster and rent a Fellini or whatever on DVD and show it at home on their own TV. Isn’t the whole idea that, you’re going to present it in a true movie theater context? Doesn’t DVD or video projection lessen the experience?

No, it doesn’t lessen things at all. As you know, technology is changing quite a bit. The quality of many formats is changing. Even video projection these days can be much better quality than it has been in the past. Remember, watching a film on TV at home, with your telephone and your refrigerator in the background, is not the same experience as an intimate venue with people there for a common reason: to enjoy a film together and maybe discuss it afterwards.

There’s nothing better than a social environment that brings people together for a common cause, and that is what this is meant to be.

Sometimes commercial theater-going experiences are very cold; they’re not meant to encourage you to talk to your neighbor. In this case, the whole gallery aspect, the bookstore aspect, the cafe aspect will invite a kind of a social experience that you’re not going to be able to get at home.

Tell us about the Cinematheque’s bookstore and cafe.

It’ll be open several hours before and after the films and between films on the weekends. There’ll be graphics displayed, for sale… rare, vintage graphics that I’ve been collecting for over 30 years…

Dana, you don’t look that old!

Since eight years old, I’ve been into this…[laughs]… and there’ll be a fireplace with a graphic above it. It’s going to look like a library that becomes a screening room when we show films…not necessarily a commercial traditional cinema… it’s mobile… for the yoga and film sessions, the chairs will move aside and it will become a studio type of atmosphere and one space will transform several times a week into different functions.

On certain nights, maybe the Avant Garde or Views From the Underground night, we’ll have more than one screen… a screen on that wall, a screen on this wall, and we might even be screening on the curtains… So it will become different experiences, different nights of the week.

I saw something, I think it was described as a “festival of film festivals,” in which the winning films from other festivals would come here.

Yes, like I said before, the idea of this space is a supplemental to all the film festivals as they come to town. So besides our in-house programming, we’ll be working collaboratively with the Miami Film Festival, the Brazilian Film Festival, the Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, the new Argentinian Film Festival… all the film festivals are invited to utilize this space.

But there was something about awarding a ?Golden Seahorse? to the best film. Is that idea still current?

But there was something about awarding a ?Golden Seahorse? to the best film. Is that idea still current?

Right… since what we’re doing is really about other festivals, the ideal, kind of ultimate, project in development after we get going would be the Festival of Film Festivals… taking the winners of all of the film festivals that we worked with and making a separate film festival with them together, because a lot of times these winners disappear. You hear about them winning, then nothing after that. Well, we’re the kind of venue that can bring them back and show them… the best of the best is still available to come and see.

Tell us about the historic building that we’re standing in and the historic street it’s located on ” Espanola Way” and the nearly one million dollar “Plaza de Espana” which is being built just outside the Cinematheque’s main entrance.

We chose this location for exactly that reason. Because they renovated this particular block incredibly, and they have put almost a million dollars into streetscape renovations here… upgraded facilities, galleries and a hotel—the Barcelona—which is going in across the street.

Is that going to be a boutique hotel? Upscale?

Exactly. Aimed toward the film and photography production market.

Tell us a little about this street and the woman who owns the property, Linda Polansky.

Well, Linda has been very helpful and very supportive. As you know, she has had a vision for Espanola Way. Linda Polansky, the owner of the entire south side of [two blocks of] the street, has been very supportive of this type of cultural idea because it’s in keeping with the original reason for Espanola Way in the first place.

What was the original concept?

Back in the ’20s, pre-Deco, the original concept of Espanola Way was kind of a bohemian village for artists and writers to congregate, to live and to work together, and this is in keeping with that same concept. It’s kind of going back to the original purposes of what this street was built for.

And when was this particular building constructed?

Nineteen twenty-five, I believe.

What else is in this building?

The Clay Hotel—originally the Matanzas Hotel—and Linda has extended The Clay [a youth hostel whose main building is a block away], so the whole block has a youth hostel kind of international feel, which also is another reason we chose this… because of the flavor of the variety of the people.

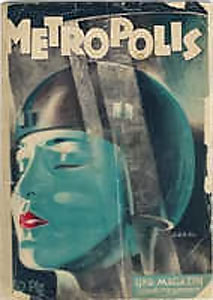

The Miami Beach Cinematheque developed out of the Miami Beach Film Society, which you founded back in 1993. Tell us about the history of the film society and some of the things you’ve done over the last decade, such as the unforgettable screening of Fritz Lang’s silent film masterpiece, Metropolis—which, as I recall, you presented in a beautifully colored print at the Colony Theater on Lincoln Road with the live accompaniment of an amazing new age orchestra from New York, playing a wildly imaginative, post-modern score, specially commissioned for this classic silent film—for 10 years you’ve been doing interesting things. Tell us about the history of the film society.

Well, we’ve been in collaborations with other cultural entities—for example, that screening of Metropolis was a collaboration with the Wolfsonian [Museum of Art and Design]. In 1993, we founded the organization and we started with historically based presentations around the beach that would bring to light really interesting things about Miami Beach.

For example, the Esther Williams Film Festival at the swimming pools of Miami Beach. We actually brought Esther in… and she’s quite a gal, let me tell you …[laughs]… she’s quite a character…we brought her in and the idea was a uniquely Miami Beach style presentation. It lasted about seven weeks and we utilized outdoor screens, which will be a big part of what we’ll do here in our courtyard and the plaza.

-from the MBC Archive

What were some of the films you showed in the Esther Williams Film Festival ? all her films?

All her films… and she opened up the festival at the Raleigh Hotel, in its heyday, with Million Dollar Mermaid; and we had synchronized swimmers in the pool, with her signing posters… which will be for sale, by the way, at the Cinematheque. That was in 1994…

You said she was a character. What did you mean by that?

Well, she…[big smile]… was quite a gal. She is an opinionated, political person. She’s very to the point and she’s very active in letting you know what she thinks…[laughs]…

Like what for example?

Well, let me give you just one story here. I remember when she wanted flowers on her table as she was autographing the posters. She goes, “Dana, these are not flowers! Joan Collins would have flowers. Those, my friend, are five erect penises. I want flowers! I want Joan Collins flowers!”

…so we had to change these dramatic lillies, which, you know, were the style at the Raleigh, into something which were much more Joan Collins…

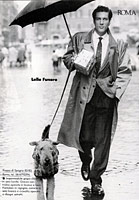

She was here for a week. But for one day, she had to go to the Bahamas for some marketing thing with her swimwear line, and she asked me to baby-sit her miniature Schnauzer. The dog had this hot pink collar and leash. I was walking it by the Lincoln Theater… and these drag queens came over to the dog and were saying, “Oh, it’s so cute.” And I said, “Well, you know, this is Esther Williams” dog.” And one of them says, “Yeah, right. And I’m Coco Chanel!”

Little did they know, it really was Esther Williams’ dog.

You said earlier that Esther Williams was political. What did you mean by that? Did she talk about war, redevelopment? What was political?

Well, come in, get her book…[laughs]…her biography will be for sale right here at the Cinematheque.

One of the things I like is that you don’t just put on a picture, you put on a show. For example at the Metropolis screening: that orchestra, didn’t the ushers wear special uniforms that you got from the 1940s style, or am I just imagining that?

No, you’re not imagining that. That was the Alloy Orchestra, and they made a whole business by supplementing silents with the unique brand of their music.

The uniform that you saw was a uniform that I brought back from the Cannes Film Festival. In its day, about 10 years ago, it used to have usher uniforms in the classic way with the pillbox hat and the buttons down… well, they were phasing that out, and I said “what are you going to do with these uniforms,” and they said “they’re going into the historical storage for the history of this festival, but you can have one of them.”

So we do have that on hand, and on special occasions we’ll be using that.

What other special programs have you done?

Well, you mentioned showmanship, and that’s very important in this particular market, because if it’s not fun, people in this particular neighborhood are not going to come.

-from the MBC Archive

And that’s why I keep going back to the uniqueness and the unusual aspects of what we will do. “Food and Film” was a five year success with us, because it combined the fine dining aspect of what Miami Beach is all about with a screening tied in with it… For five years we partnered with Gourmet Magazine from Conde Nast and they brought in a lot of their sponsors to help us work with the chefs to create a meal tied in with the film.

And it helped raise money for this [Cinematheque project] along with the Academy Awards nights, which is an annual thing we do with TMG Productions. And that is now officially sanctioned by the Academy Awards itself. They choose one party per city that’s impressive and interesting, and we were chosen as the officially sanctioned party… so therefore when you come you get the official Academy Awards program and you get the links to the Academy Awards sites. So that’s one of our major fund-raisers that’s helped make this all happen.

Where were you born and when did you fall in love with the movies. And do you remember the first movie you saw?

I was born in Sante Fe, New Mexico, and grew up in New Mexico, went to school in Southern California, and ended up in Europe for 10 years modeling.

All my life I’ve been a film buff. I’ve been interested in the creative aspects of film and even the construction elements of film, rather than merely the entertainment aspects of film, believe it or not as long as I can remember.

Nineteen sixty-four—Mary Poppins—in a drive-in theater, I remember being fascinated by the special effects and how she “flew.” Rather than getting involved in the story, I was thinking technically and artistically about how they were doing that. That was when I was five years old.

And I started collecting graphic and historically significant documents right about the same time. In fact, the souvenir program collection I have started in 1968 with Carol Reed’s Oliver at the Bonanza Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Now, for economic reasons, souvenir programs are given out at premiers only. But at one time, during the fifties, the sixties, and even going as far back as the twenties and thirties, when movie palaces were in vogue, there were dramatic marketing ways to attract people and to keep them interested, and souvenir programs were one of the biggest.

About your modeling years, weren’t you based in Germany for quite a long time?

Well, actually I was based in Paris and Milan. I ended up going to Europe to test because an agency in Santa Barbara sent me. I thought, OK, give it three months, I’ll have fun—I ended up staying 10 years.

You also have amassed a museum-quality collection of historic movie posters, souvenir programs and other movie memorabilia, much of it collected in Europe while you lived there during your modeling years.

Models have a lot of freedom… traveling from place to place. And my film fanaticism went crazy with the availability of really beautiful historical materials. Like, for example, the souvenir program traditions of Austria, Denmark, Spain, and France.

Where did you find these things?

I discovered them in places like flea markets. I didn’t realize there was a whole group of collectors… I ended up collecting them for years and years, and I ended up with some of the rarest materials—that even they acknowledged—such as the original program for Metropolis.

My collection basically tells the entire history of the cinema from 1895 to today, so Thomas Edison with all the experimental work done at the end of that century, his documents, his programs, or at least announcements of his screenings. I went out of my way to choose the highlights and collect them to tell the whole history of the cinema. So I’ll be supplementing our screenings appropriately with some of these stories of cinema.

Some of your pieces have been shown at the Wolfsonian Museum. Because it is a valuable collection, where do you store it? What would be the security aspects of having some of these things here at the Cinematheque?

Well, they won’t have a permanent home here, that’s for sure. Certain ones that I have duplicates of maybe will be on permanent display. As you see around the room, there are possibilities of display cases, and as we present films, I’ll bring in some of the rare items.

Your bio says you have two undergraduate degrees from the University of California at Santa Barbara—one in Cinema, emphasizing film history, aesthetics, and criticism, and one in Fine Arts, emphasizing graphic arts with photography and photolithography. Did you have to write a senior thesis for your film course, and if so what was the topic?

I actually wrote several theses. Our film program was very liberal: they allowed us to create projects how we saw fit and since I was a double-major, a lot of my work was graphically oriented. I designed the magazine in college, the film magazine, and also developed the summer film institute. And at the same time being the graphic artist for it and handling all the visual elements. So my theses projects were always about the color usage in cinema or the graphic use of editing technique. It all went to the construction and aesthetics.

About what year was this?

This was ’82, the same year I used to work at the Academy Awards.

Tell us about that.

Yeah, well, I was working at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion for the Academy Awards; that was quite an experience.

You were a greeter?

It was an unusual job. They needed people in the lobby just basically just to help people feel at home and welcome.

There I was, as a 21 or 22 year old kid greeting people like Paul Newman, Raquel Welsh and Cher—and, you know, Dustin Hoffman, you name it, they came through those doors. I did end up at a barbecue at Cher’s house among other… several wild things Hollywood people do.

That begs the question: What are the “wild things” that Hollywood people do?

…[laughs]…Well, hopefully, they come and appreciate cinema here at the Cinematheque…

Going back to the school thing, did you ever make or act in any student or professional films, or how about TV commercials during your modeling career?

Well, since my emphasis was aesthetics, theory, history, criticism, I had very little actual production experience.

However, I was more behind the camera than in front of it during my student days. I was the apprentice of Robert Boyle who was a production designer in Hollywood. In fact, he designed some of Hitchcock’s films, like The Birds and Marnie. He kind of took me under his wing and taught me the craft. But I discovered I really was more interested in the appreciation of film rather than the production of film.

-from the MBC Archive

For those who may not know, what is a production designer?

He designs all the creative aspects that have to do with sets, the interior design, the exterior design, sometimes the composition, working with the cinematographer.

Most of my work done with Robert Boyle was with pre-production; it had a lot to do with conceptual designing, ideas, based on research on the project and that has a lot to do with the architectural design of the set.

Your bio says your background includes management of the Arlington Center for the Performing Arts in Santa Barbara, and The Red Rock 11 Theatres—at the time, it says, the world’s largest theatre complex. Tell us about your experience as a theater manager and impresario.

Well, this performing arts center I worked for in Santa Barbara was actually a movie palace—a 1931 Fox movie palace, which became a performing arts center because of the typical economics of movie palaces turning into arts centers. So my favorite aspect of that was the retrospective film type of programming between the B-52s or maybe Tokyo Ballet, or everything from Leontyne Price to David Byrne and the Talking Heads.

My favorite was always the avant-garde screening that attracted fewer people than the 2,000 people that were there the night before. [laughs]

You’ve had to raise a lot of money and organize a considerable amount community support to fund the Film Society and this Cinematheque. How much is the renovation of the Cinematheque space going to cost?

Well, the renovation has been a lot bigger project than we ever dreamed or wanted. This space, which we fell in love with, unfortunately had its problems. It was virtually crumbling. It was a storage unit for years, so it had to be completely brought up to code. The walls were falling apart; the ceiling was caving in. Little by little it came together thanks to Linda Polansky who has been instrumental in helping fund the renovations.

Our side of it came from private donations, a couple corporate sponsors here and there, and the generosity of people realizing the importance of helping at the beginning, which is a lot more difficult than bringing them on to promote funding for programming.

For example, it’s a lot more difficult to convince someone to help you put in a $6,000 air A/C unit than getting a lot of acknowledgement at a sexy, fun event.

You seem to have been pretty successful over the years in raising money. I mean, wouldn’t you say so?

[Barbara Permagament, the Film Society’s chairman of the board, interjects]: He’s the hardest working person I’ve ever known in my life… dedicated beyond dedication…

[Dana replies]: Well, the fund-raising aspect comes from the Board’s help as well… the Board is the base of the fund-raising activities.

Well, let me bring you back to one part of my question: how much is the renovation and rental of this space costing?

It’s hard to put a dollar value exactly on a project like this because it goes through so many phases, but like I say the landlord has handled a lot of that. We’ve helped a lot with some of the design aspects we’ve chosen: these are some of the less expensive renovations.

So our main cost was really more the rent, which eventually had to start, naturally… inevitably. She can’t go on forever giving us free rent. So of course the rent has started and we’ve been raising money.

What sort of rent is it?

Well it’s surprisingly good if you compare it to Lincoln Road prices…

How much do tickets cost?

Tickets are going to be typical of movies, probably from $8 to $10. Membership gives you a discount on that ticket. Special events will obviously be more if it includes a meal or includes maybe a lecture or a yoga class.

There’s a wide variety of membership starting at $50. That’s Basic Membership. And $100 membership, what we call Premier Membership, gives you even more perks. And then the Founding Circle, the people who have really helped us out either with in kind donation or cash donation, those starts at $500. We’re still developing that, by the way, if any of your readers are interested, we’ll be happy to add to our Founding Circle, and see how they can fit in any way they can.

When and how did you come to reside in South Beach?

As a model…the German market usually shot here…and that was in the mid-80s when South Beach was a combination of crumbling buildings and new directions. So I ended up here. I became friends with several locals, and I decided this was European and pedestrian-oriented, and interesting and varied and cultured, just like I’d been used to in Europe ? not exactly, obviously with a more Latin side to things. But it’s not Middle America…

Italian Vogue

I understand you were a major house model for Gianni Versace and worked closely with him. Tell us about that.

Well, yeah, I worked with Gianni for five years, doing all of his shows, the male shows and as a supplement to his female shows as well and vice versa. He used to sprinkle his favorite female models in male shows and mix his male models into his female shows. And sometimes his photo shoots. I debuted his first couture line for men in 1986, I was the main model for that, the fitting model for that . . .[the murder of Versace on the steps of his South Beach palazzo] was devastating, of course. I was actually here that day and it was just a horrible thing that happened. And it changed the whole South Beach scene.

You’ve been here quite a while. How do you see the development of South Beach? Many people contend it has become less bohemian, much more mainstream, and far less artistic than it was a decade ago.

On the other hand, this part of South Beach, the picturesque Espanola Way shopping and dining district, is booming now. And there are still quite a few artists? studios in the Espanola Way Art Center building that Scott Robins Companies owns on the corner of Espanola and Washington Avenue.

What’s your take on South Beach’s development direction and the role of artists and art institutions in its commercial success?

Well, there’s been a combination of good and bad happening in South Beach. The gentrification of the area is good in many ways. It brings money to the area. However, it pushes out the artists and the cultural institutions.

Lincoln Road, as you can see, is basically, slowly, little by little becoming kind of a shopping mall. The day the Miami City Ballet practice space went out and Victoria’s Secret went in, was very symbolic of what Lincoln Road has become.

To me, Espanola Way is still an escape from the commercialization and standardization of things.

It’s got individual charm, it’s got the bohemian aspect, and now with the renovation—as I said the good and the bad—it’s enabling a combination of markets to come and enjoy it. That’s why I think we fit in, and luckily we found this space just in time.

Do you have a long-term lease?

Luckily we do… ten years.

Do you think City Hall, the politicians, and the real estate community share your vision? Or will they say, ‘Gee, this is the perfect place to put in another Gap or other chain store?’

I don’t think Gaps will ever come to Espanola Way, because it’s ? there’s not enough foot traffic here. It’s in the middle of everything, but it’s an escape from everything.

This street leads into a residential neighborhood. This particular west end is very residential as well as being commercial now. You know the nightclub boom in South Beach, which was a great thing economically for South Beach, was a wonderful thing that hit this town. However, there’s always been a need, I think, for small cultural activities, along with the major institutions, the anchors, if you will of the Wolfsonian, the Bass Museum the Jewish Museum . . .

There’s always been a need for kind of a St. Germain Des Pres or West Village atmosphere, and this is where it should be.

South Beach is changing with the addition of hundreds of millions of dollars worth of high-rise, high-end condos on the water. Despite a worldwide recession, these luxury condos are selling like hotcakes. And for many of the wealthy buyers from around the world, these South Beach apartments are their second or third homes. Generally, these folks seem less enamored with the nightclub culture of South Beach than the twenty-something trendoids who congregate in the clubs. At least some of the owners of the new condos are protesting powerfully against the endless noise in their neighborhood. Whatever the merits of that controversy, it’s clear South Beach’s demographics are changing. What does that mean for the film society? Are these well-to-do condo dwellers interested in the cinema?

Well, I think it’s becoming a more well rounded neighborhood with a variety of locals, rather than a party town full of partiers. The condos are bringing a different type of person… looking for interesting things to do. They obviously enjoy the nightclub atmosphere and what it can give them — but I think they’re looking for that something more that they can get in other cities like New York.

A lot of these people are New Yorkers. They’re used to neighborhoods with galleries and cafes and cultural things going on. And this is exactly the type of project I think a lot of these people will appreciate.

When you worked as the concierge at the rather chic and very trendy Astor Hotel—which is near the both the Wolfsonian Museum and a whole string of nightclubs on lower Washington Avenue—did more people ask you about going to the clubs or going to the museum?

Definitely the clubs… [laughs]… they come here to party.

But I enlightened many people by mentioning the Wolfsonian was right across the street and surprising them with the world class aspects of what’s right across the way.

And what about requests for escort services—call girls and call boys—isn’t that a part of the famous South Beach mix?

That’s definitely part of it, but if you ask any professional concierge they’ll tell you that there are two things they don’t do: and that’s offering connections to prostitution and to drugs. So we’re not pimps and we’re not drug dealers. We’re expediters of a good time in other ways.

With the chic boutique-style hotel [like the Astor], luckily we got a wonderful variety of upscale and interesting people as well as interesting bohemian artist types — that’s the best thing about working in the hotel industry. And that’s one of the things that kept me interested in staying in South Beach.

What were the most common requests you’d get as a concierge?

Where are the best clubs? Where are the best restaurants? What’s the thing to do tonight, and how can you help me get on the guest list?

What were the most unusual requests you have ever received?

Well, the chic, little boutique-style hotels attract a kind of celebrity clientele — and I’m not going to name any names. But sometimes the more famous someone is, the more, kind of… detailed their requests are.

You know, some of hotel staff maybe would complain about the details of a request, but I kind of find it interesting and challenging.

So one particular celebrity guest of ours, I kept an entire list of his absolute, adamant requests that must happen every time he comes to town, so you should realize and know that without him asking. Things like, for example, no safety pins on his dry-cleaning.

And no strawberries near the scrambled eggs. Just a whole list of unusual things. So as long as you knew them, everything was great.

How long were you a concierge?

Well, right now I’m still working at The Nash as guest relations manager.

I actually opened The Astor, with [owner] Karim [Masri] back in 1995 and opened The Nash with Laura Sheriden and [owner] Gregg Lurie, who’s one of our sponsors by the way.

So in addition to your work with the film society and Cinematheque, you do what most people would call a full-time time job, like 40 hours week at the hotel?

See, now you’re learning the complexity of a non-profit organization with limited funding. Someone’s got to work; someone’s got to have a life aside from it. Luckily, the owner of the hotel is understanding of what I’m doing and is helping out.

MIAMI BEACH CINEMATHEQUE MEMBERSHIP

There are nine levels of participation in Miami Beach Cinematheque, from $50 Annual Memberships to $25,000 Founding Circle Members whose names will be prominently displayed on a Founding Circle Members plaque at the Cinematheque.

Each of the nine membership levels provides a different type of acknowledgement, and there are numerous ways corporate level members can receive exposure and positive publicity.

For more information visit: Miami Beach Cinematheque