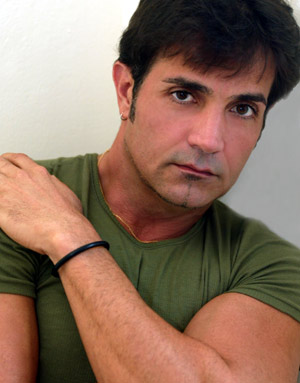

Once among Cuba’s most acclaimed professional dancers and now a successful artist in Miami, Noel is presently settling into his newly renovated 1927 Mediterranean Art Deco house in a Bohemian enclave just off Miami’s Biscayne Boulevard. Now, more than a decade after South Beach blossomed into a global cultural and creative phenomenon, Noel’s cutting-edge artistic prowess remains at the forefront of Miami’s art scene as the migration from Miami Beach continues across Biscayne Bay.

Born in Havana in 1958, Noel grew up in a family of professional artists. His mother and grandmother were dancers, while his father was a painter and photographer. He attended the prestigious National School of Art, where he studied dance and dabbled in art. He came to the U.S. in 1981, by way of Costa Rica, after a promising early career with the most important dance companies in Cuba. In 1986, he joined the Boston Ballet and also toured with other major companies including Joffrey Ballet and American Ballet Theater.

After a dislocated knee ended his dance career in the late 1980’s, he turned to art as a vocation. Since then, his work has been internationally acclaimed and risen steadily in value. He is presently at work with a fellow Miamian, pop art superstar Romero Britto, on a collaborative work that will be unveiled early next year.

How did you become a dancer?

I had dreamed of being a dancer since the day I was born. There was a ballet school in my house, so I had no choice. I grew up in a theatrical family. My grandmother was the official dance teacher for the national opera company in Havana. My mother was a dancer. My father was a photographer and painter. I had the good fortune to be born into a family of professionals. They don’t push you. You have to come out on your own and show that you have talent, and then they encourage you.

How old were you when you started dancing?

I was four. I would try to imitate the students in the ballet classes.

When did you actually start studying dance?

At five.

When did you become a professional?

That’s an interesting question, because when you are a dancer, you are a professional from day one. If you’re not a professional from the beginning, you’re never going to be a professional. It becomes a very intense discipline. In terms of the economics, though, I became a professional dancer at 15.

What happened with your dance career when you came to the U.S.?

Before I came to the U.S., I lived in Costa Rica for seven months. I danced as a principal and taught with the national dance company. Then I came here to Miami, in December 1981, and I worked with the only two companies really working here back then, Dance Miami and Ballet Concerto.

You came just after the famous Mariel boat lift. That must have been a strange time in Miami.

I like the fact that I lived through the entire evolution of Miami, from the beginning.

Why did you become a dancer in the first place? What so appealed to you?

Why did you become a dancer in the first place? What so appealed to you?

I don’t even know. I just felt it. Like I said, I grew up around singers and pianists, dancers and artists. So, it wasn’t a matter of “becoming” a dancer—it was my dream from the beginning. I can’t even explain it. I just felt from a very early age that it was my passion, my destiny.

When you came to the U.S., how far did your dance career go?

I moved to Boston and went to work with the Boston Ballet soon after I came to the States. I was in Miami a very short amount of time. I got to realize that there was not much support for the arts in Miami. It was a different city back then. There was not much going on at all. So, I heard from dancers and others who passed through that the only way to get a good opportunity was with one of the really good dance companies in a big city up north.

How did you end up picking Boston?

I said to myself, “I’m going to go audition for the first company that comes down,” because no matter where they come from, it has to be better than this. It was tough.

So, the first company to come through was the Boston Ballet, with Rudolph Nureyev performing Don Quixote at Dade County Auditorium. I went and auditioned and got the job. I danced in the chorus for some of the remaining performances with Nureyev. I ended up being with the company for two years.

Then what?

I wanted to explore more about myself in a different style of dance and repertoire. In Cuba, we do all different kinds of dance, not just classical. You also get to dance a more open repertoire. If you just do classical, classical, classical—after a while it gets very robotic and you don’t feel it. So, there was a company in Boston called New England Dinosaur Dance Company. They did “contemporary” modern dance. They came to see me dance with Boston Ballet and then asked me to join their company. I was there for four years and I really enjoyed it.

What happened next?

Then I started doing freelance work in New York, both classical ballet and contemporary ballet, with small companies. And I was fortunate enough to be taken on as a student by David Howard, who was the most important teacher of his time, in the early 1980’s.

He gave me a scholarship, and the first day I walked into the professional class, there was Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gelsey Kirkland and all these famous dancers. I was surrounded by some of the greatest dancers in the world. So, I became a better dancer and made great connections as a result of him.

That’s when I started working with Joffrey Ballet. I started taking classes with them because that was my favorite company. At the time, I was dancing with American Ballet Theater, but my knee was starting to give me problems. I was getting old for a dancer. I was 28.

How did the knee injury happen?

It was the result of working the body to such a level that it’s not human. No matter what kind of shape you’re in, your body suffers. My knee got totally destroyed as a result of the extreme pressure that is put on a dancer’s knees. So, I had to face a very intense, strong reality. My insides told me that I had to quit, that this was it. It took a while though, because I didn’t want to face what was happening. It took a good five months for me to make the decision.

What finally caused you to make the decision?

I dislocated my knee and that was it. I saw all the doctors, and I could have had an operation, but I just knew that was it. I didn’t want to go through all that just so I could continue to inflict pain and physical damage on myself.

It’s a tough profession, isn’t it?

It’s a very cruel career, because you realize when you are a young person that you have all this energy, but it becomes so intense, that at a certain point you just have to let it go. At an age when most people are just starting to work at the career they want, your career is over.

How did the transition to an art career happen?

The art was a total accident, a pure accident. I had always painted. It was my hobby. My father was a photographer and artist, so it was in my blood. I was around art all the time, and I actually got started by doing sets and costume design for dance productions in Cuba. So, when I quit dancing, I didn’t know what to do with myself. I was trying to become a normal person because dancers are not normal, I can tell you that. Dancers live in a whole different world and have a whole different philosophy of life. You live in a theatre, so you live the life of the theatre. It’s not real.

So, when I decided to quit dancing, I had to realize that there was a whole other kind of life that normal people lead. I had to come up with a way to enter that world. I tried every job in the world, but none of them were for me, from working in a bank to working in a store. I was in a shirt and tie every day and I just felt that it wasn’t me.

How many jobs do you think you went through before you decided to become a professional artist?

At least 15.

How did you finally make the transition to art?

I needed some time to think about what I really wanted to do, so I took a job in Boston working in a restaurant, and I did it for two and a half years. And I started painting on the side because painting was the only thing that kept me in touch with my creative background.

But you needed to get free of dance?

Yes. It’s an obsession, and once you get outside that world, you realize the extreme things you had to do to exist in that world, which isn’t natural and isn’t real. But it becomes all-consuming. You know the best way I can describe being a dancer.

It’s sado-masochism. It really is. If you don’t feel the pain, you’re not working hard enough.

But doesn’t a general ethic of hard work and pushing yourself carry over to the art career?

Yes, that’s the part I’m extremely thankful for. The discipline and focus that you get as a dancer are tremendous assets in your life. Those are the most positive elements of a dancer’s life.

How long were you painting on the side before you decided to get serious about it?

About a year and a half. I was working out my style, and I got to realize that painting was my salvation. I knew that the energy that brought me into this world made me to be an artist of some kind, a person in the arts. So now that I couldn’t dance any more, I had to refocus my artistic instincts on another medium of expression. I knew that I wasn’t going to be happy otherwise.

When did you sell your first piece?

I was painting in Boston and I started to accumulate a lot of work. One of my friends came to my house and saw how much stuff I had hanging around the house, and she said, “you’re very good at this. Why don’t you focus on art as your new career?” I said, “Every artist I know is starving, and I don’t want to have to go through that.” I’m doing it as a hobby, as an outlet.

But people kept insisting that I show my work. Then a friend of my friend’s opened an art gallery in Provincetown, Massachusetts, in 1986, and he suggested that he organize a show of my work. He sold 13 of 15 pieces on the spot, and the rest within a few days. It was really amazing.

How much did the pieces sell for back then?

Three hundred dollars. I had done the show for the heck of it, but then after I saw that I had sold all this work, I said to myself, “maybe there’s something here. Maybe I should pay attention to this opportunity.”

So what happened next?

I just started doing it and kept doing it. Then people from all around Boston started calling me to do more shows and then events, and then posters for events. And before I knew it, three years had gone by and I was in the spotlight again—as an artist instead of as a dancer.

Then you opened your own studio in Boston?

Yes, in the fall of 1987. I painted a lot and I started showing a lot. And that lasted for three wonderful years.

How do you describe your style?

My style is technically figurative cubism. But I’m always changing—all my work is an exploration of the male or female body.

How often do you do shows now?

Once a year, in Boston and Provincetown. I have a huge following in Provincetown.

What does your work sell for now?

The smaller pieces, original oils, sell for anywhere from five or six thousand to twenty thousand. The larger pieces sell for more. Giclee reproductions sell for between six hundred and twelve hundred dollars.

And you sell everything you produce?

Yes. And I also get commissioned to do a lot of work, from both corporate and private individual clients.

When is your next exhibit?

Well, I just finished one in Provincetown, not long ago, but my next one is going to be a very interesting one. I’m doing a collaborative work with Romero Britto. We’re going to actually work together. We’ve been talking about it for a few months. I think the two of us coming together will create a whole new world, because our styles are so vivid.

When is it going to happen?

At the end of February.

Where?

At his studio and gallery on Lincoln Road in Miami Beach.

Is this the first time you ever collaborated with another artist?

In this way, yes, but I have collaborated in other ways with other artists.

But this will be the first time that I actually paint with another painter on the same canvas. It’s very exciting for me.

What do you think of the art scene in Miami these days?

I’m happier, because we have grown, and there’s a lot more to do than there was when I got here in 1981. But the art scene in Miami is really still in diapers. It’s very young.

But I’m encouraged, because many of the writers and dancers and writers and filmmakers and painters don’t feel the need to leave Miami any more to go out and have a career. It can be done right here. And that’s a great thing.

Do you think the art scene that does exist is moving over to Biscayne Boulevard?

Oh yes, totally. Biscayne is truly now the next South Beach.

What do you think has happened to South Beach?

The beach is over, unfortunately. Take it from one of those persons who are to blame, because we put it on the map, we made people pay attention to it. But then events got beyond our control. So, everybody I knew when I first got here is gone. Long gone.

But I still love the Beach. I have this very intense connection with the Beach, only to find out years later what the connection was—I was conceived at the Eden Roc Hotel.

What caused you to make your decision to move off the Beach?

I just cannot take it any more. I don’t feel like it’s a happening place any more. My Beach is gone.

Is there a chance the Beach will re-create itself over in this area, along Biscayne?

Oh yes. It’s already doing it—it’s happening already. Just look at what Mark Soyka has done with Soyka and the little community that has been created.

What’s your driving philosophy of life now?

I think it’s the same thing that has always driven me. My philosophy is that no matter what, life is a wonderful experience.

Even the bad stuff?

Even the bad stuff, and I’ve had my share. Plenty of bad stuff. But no matter what, life is a wonderful thing, a great experience.

Do you have a philosophy of art?

I don’t know if you could call it a philosophy. I think it’s more of a feeling.

Why do you paint what you paint?

I don’t know. You’re not supposed to know. I can’t say “I paint because…?” I just paint.

You’re self-taught?

Yes, but it’s in my genes. I come from a family of artists and performers, but I took some courses at the National College of Art, which is in the same building where I studied dance.

How are you different as an artist from who you were as a dancer?

As a person, there is a huge difference. I’m a lot less egotistical. There are other people living in this world besides me. That is how a dancer lives. You have people telling you how good you look, and how wonderful you are. You have photographers taking your picture all the time, always showing you in perfect light. And you are surrounded by mirrors, twenty-four seven. And so you get to a point of being so obsessed with yourself and your art that nothing is ever enough.

How do you adjust away from that once you stop dancing?

You have to correct yourself. You have to learn to be human again. And it is hard. My major number-one down period in my life was when I quit ballet. I really felt like I was let go from a great height and really hit the ground. I had to learn to be human from the beginning again, because I grew up being an inhuman dancer, not a human person.

What’s your next big goal?

Just keeping happy and working, just doing what I’m doing. My biggest goal is to be sure that I’m happy and that I’m happy doing what I’m doing.